Iran. Although home to one of the world’s oldest civilizations, (dating back more than 5,000 years), since 1979 Iran is most commonly known for the Islamic Revolution that toppled Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and took 66 Americans hostage, holding them for 444 days. Iran is daily in the news, with its military activities in Syria and Yemen, its support of Hezbollah, endless negotiations over its nuclear program, and its detention of reporters like the Washington Post’s Jason Rezaian. “Death to America” is a chant heard in televised demonstrations in Tehran, setting the outside view of Iran as a hostile one to the West.

In contrast to this public view, I’ve been fortunate to know many Iranians who live in the United States, as well as abroad. Without exception, they love the United States and the common theme among them is a love of life and all it has to offer. With these contrasting experiences in mind, I determined to make a trip to Iran.

Getting into Iran as an American is no easy task. Reams of paperwork, multiple passport photographs, and multiple visits to the Iranian Interest Section in Washington, D.C., are required. Iranians work on a different time scale, and waiting is part of the process. The government of Iran is suspicious of one’s prior travel, and does a thorough investigation into who you are. (It’s possible to go with a tour group, but tours are heavily monitored by the government and I wanted freedom of movement.) In the end, it took me over a year to obtain permission to visit Iran.

Visa in hand, I scheduled a flight. Since 1979, Iran has been subject to a range of economic sanctions, including ones which eliminated direct flights from the United States. Iran is not a close destination. My flight took me through Istanbul, Turkey—with a 7 hour layover. Layover included, total travel time from Dulles to Tehran was 20 hours.

Arriving in Iran was a bit of an emotional let down. Based on my experiences with Iranian officials in the United States, I had expected a high degree of security and curiosity about an American's arrival. At the airport, I found only a single disinterested official at Passport Control. A glance at my visa, a scan into the computer, and I was on my way without even eye contact or a single question about the purpose of my visit.

Tehran is one of the biggest cities in the world, with more than 17 million people. It is spread out over

more than 200 square miles, and the airport is more than 30 miles south of the city. Tehran is a city and Iran is a country which are impossible to pigeon-hole, with variety and diversity which are difficult to comprehend.

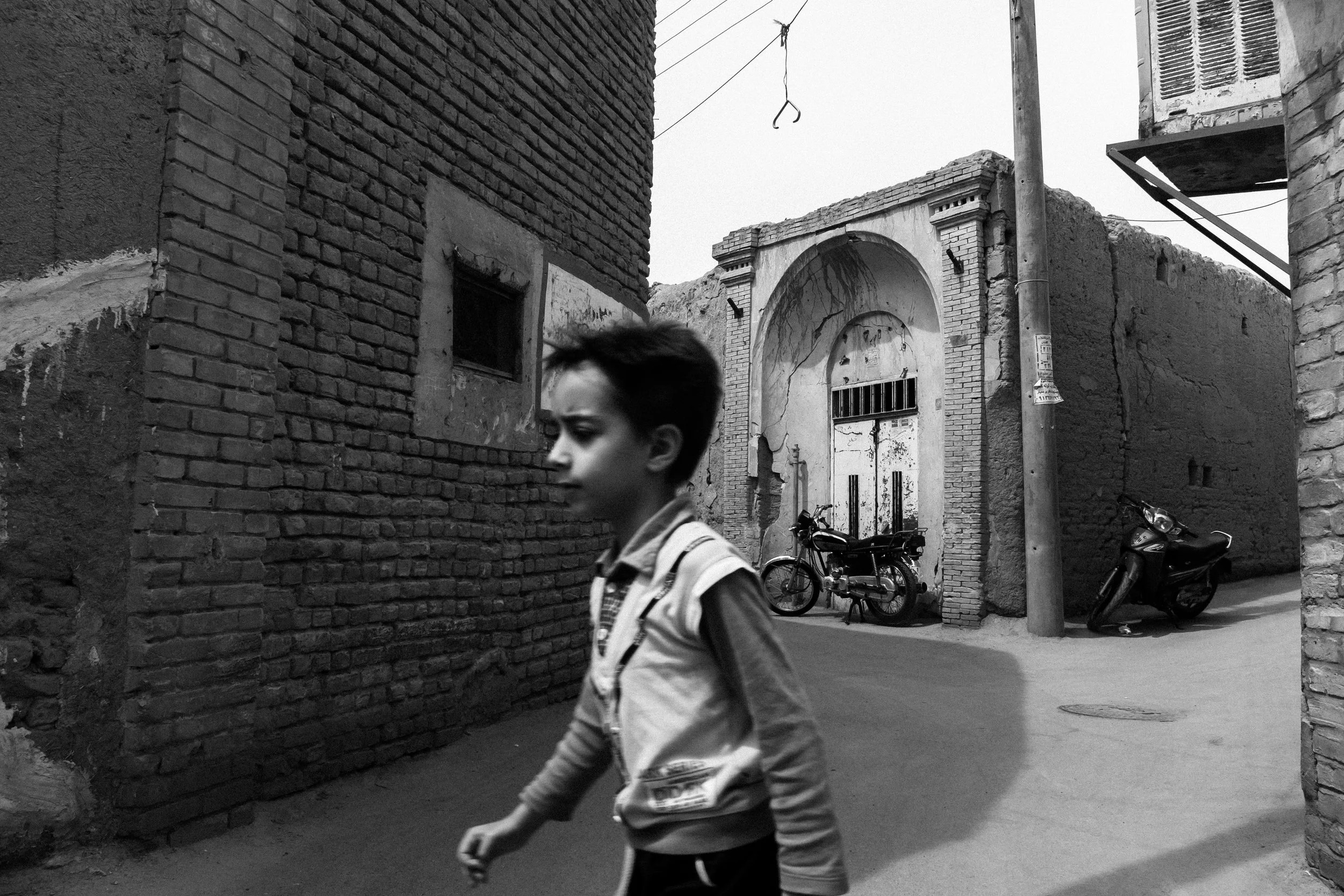

Being inside Iran is much different than hearing about it from the outside. While not an easy country to absorb or function in, the people are warm and welcoming, and there is a vast range of poverty and wealth among a people who have been isolated from much of the West for more than a generation. (Although only the United States and Canada have official sanctions against Iran, the complexity of those sections affects travel, banking, postal services, and foreign businesses who also do business with the United States.) Despite all the international conflict concerning Iran's political role and its present history, the people within Iran continue to flourish in an environment that's all their own.

Working as a photographer in Iran is beset with challenges. I was based in the northern part of Tehran, making day trips to other parts of the country. Each place presented unique difficulties and opportunities, but there were common themes.

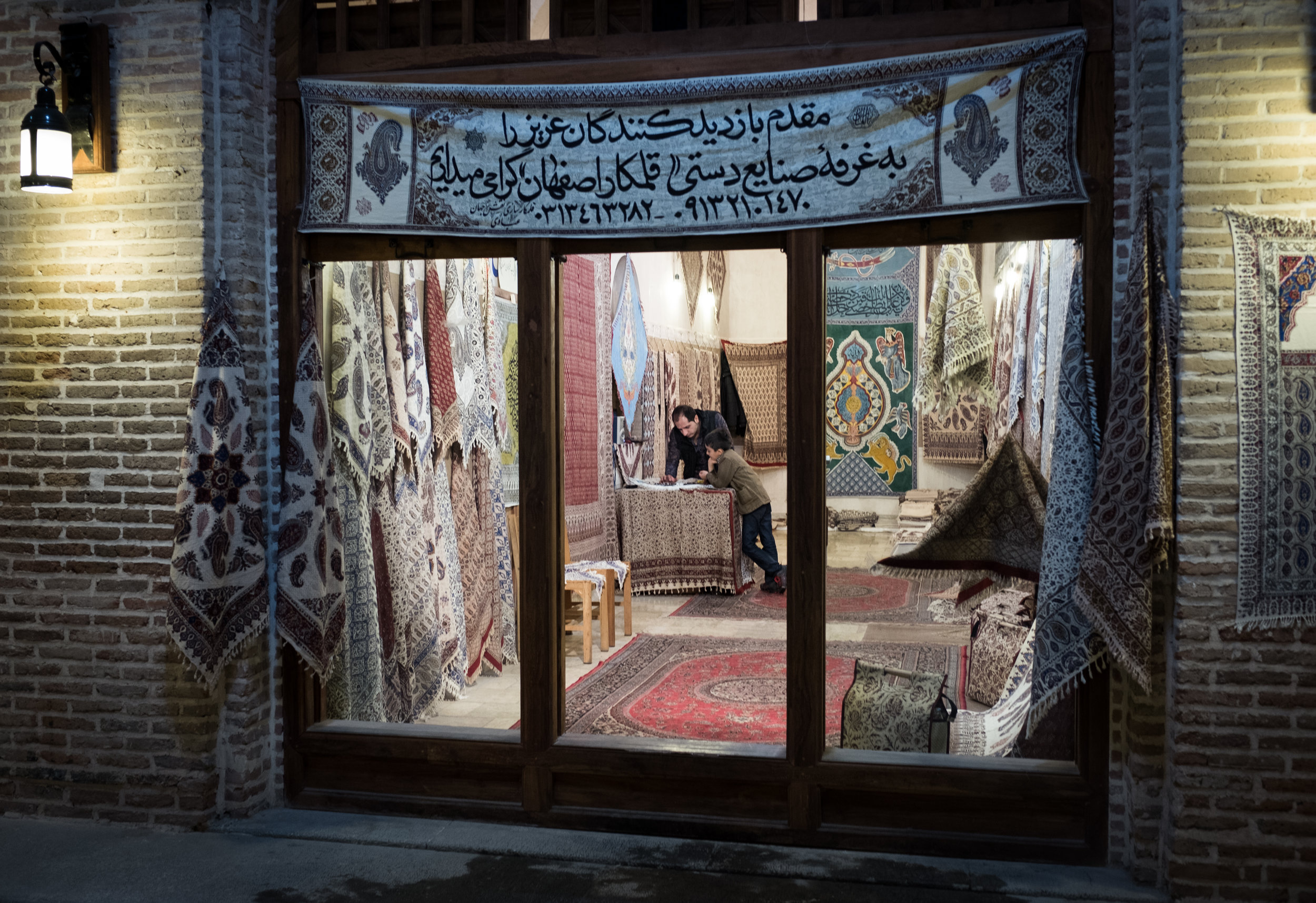

Iran is a very foreign place to anyone who's not Iranian. Not only do the Islamic rules affect all forms of behavior, but the language is unapproachable. Rather than the West Germanic of English, which is structurally shared by all European languages, Farsi evolved from an offshoot of Indo-Iranian. So while it's possible as an English speaker to decipher a subway map in Germany or France because of common characters and grammatical conventions, it is impossible to make any sense of Farsi unless you know it. (Spoken Farsi uses some Arabic and French words, and written Farsi shares much of the Arabic alphabet, but the meanings of the words are often so different that even when someone who knows Arabic is able to read Farsi, it won't make any sense.)

The language challenge is not to be underestimated. With both the written and verbal language being so different, it's nearly impossible to use signs as landmarks or even indications of locations. There is some iconography (such as for bathrooms), and many signs have English on them. Iranians who have attended private school or been educated abroad often have excellent English, but the vast majority of the population doesn't speak English at all.

Iranian culture emphasizes graciousness above all else. Religious, political, and class differences all fade into the background when it comes to an Iranian welcoming you to their home or business. Generosity is the strongest impulse any Iranian you meet will have. No matter your problem or question, anyone you ask will go above and beyond to help you.

That said, each ethnic and religious group has its own rules of decorum, and one has to be cautious to stay within the bounds. Moreover, many places in the country are off-limits to photography, and photographing government officials of any type is unwise. The government has no problem arresting first and sorting out the questions later.

Traveling to places where one doesn't speak or read the language is not uncommon. Traveling to places where one has little chance of grasping the culture, however, is rare. It's extremely stressful and overwhelming, taxing one's creativity as well as one's emotions.

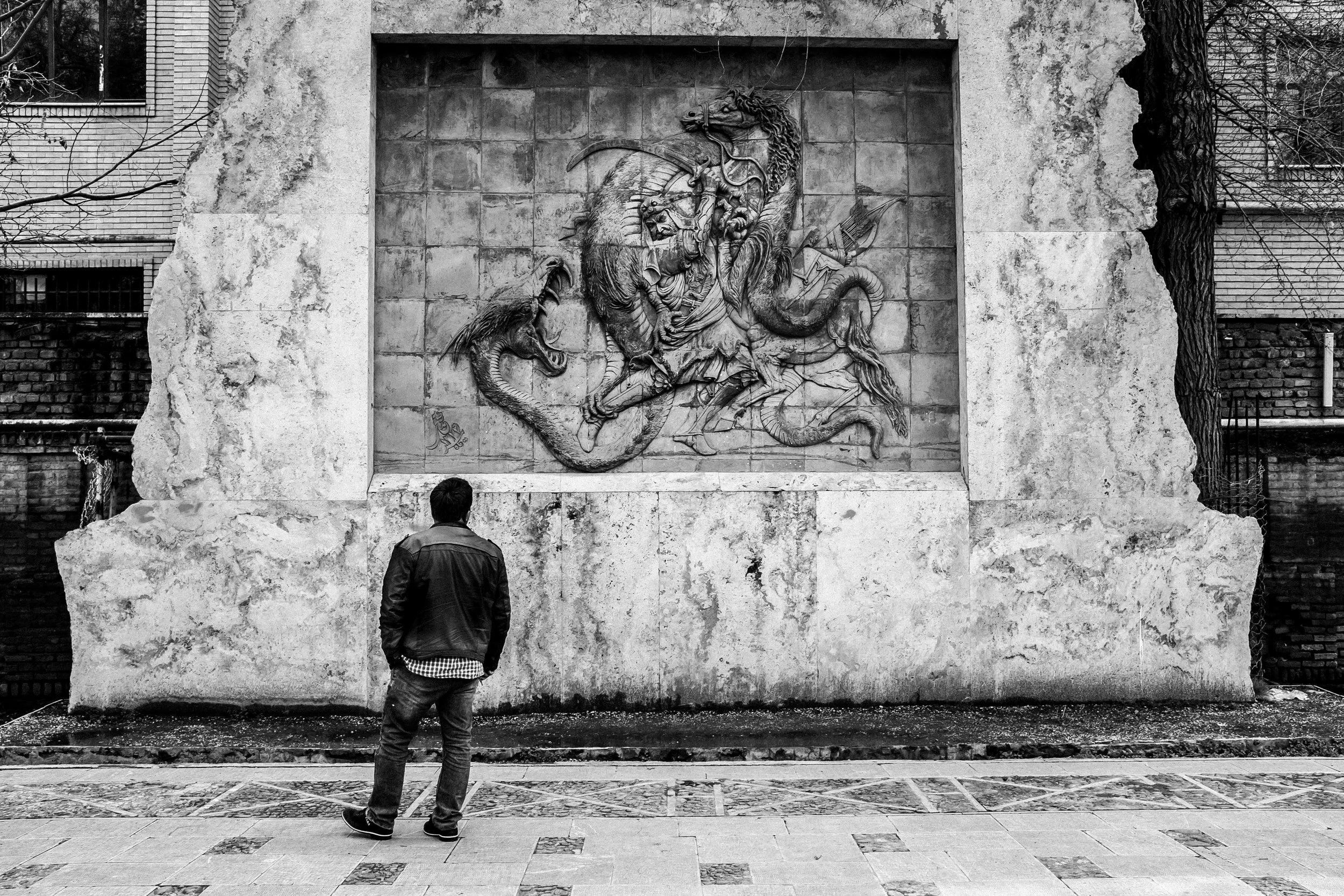

But it’s also liberating to be lost. Removed from even absentminded awareness of so much of what's going on, the mind has little choice but to double its efforts to observe and make sense of things. Lost, it’s easier to perceive humanistic patterns. Lost, it's easier to put attention on the gestalt. Lost, it's easier to let your deeper self emerge.

The aesthetics of lostness have a quality of their own. The feeling on many levels is one of isolation and disconnectedness. Like any state of mind, these aspects are revealed in the work. My interpretation of the images I made in Iran reflect this: isolated moments; overwhelming scale; and a puzzlement of things. I endeavored to embrace the lostness, however, because the alternative was to find a false narrative which would devolve into stereotype. In the lostness, I sought the commonality of humanity instead of looking for the superficiality of difference.